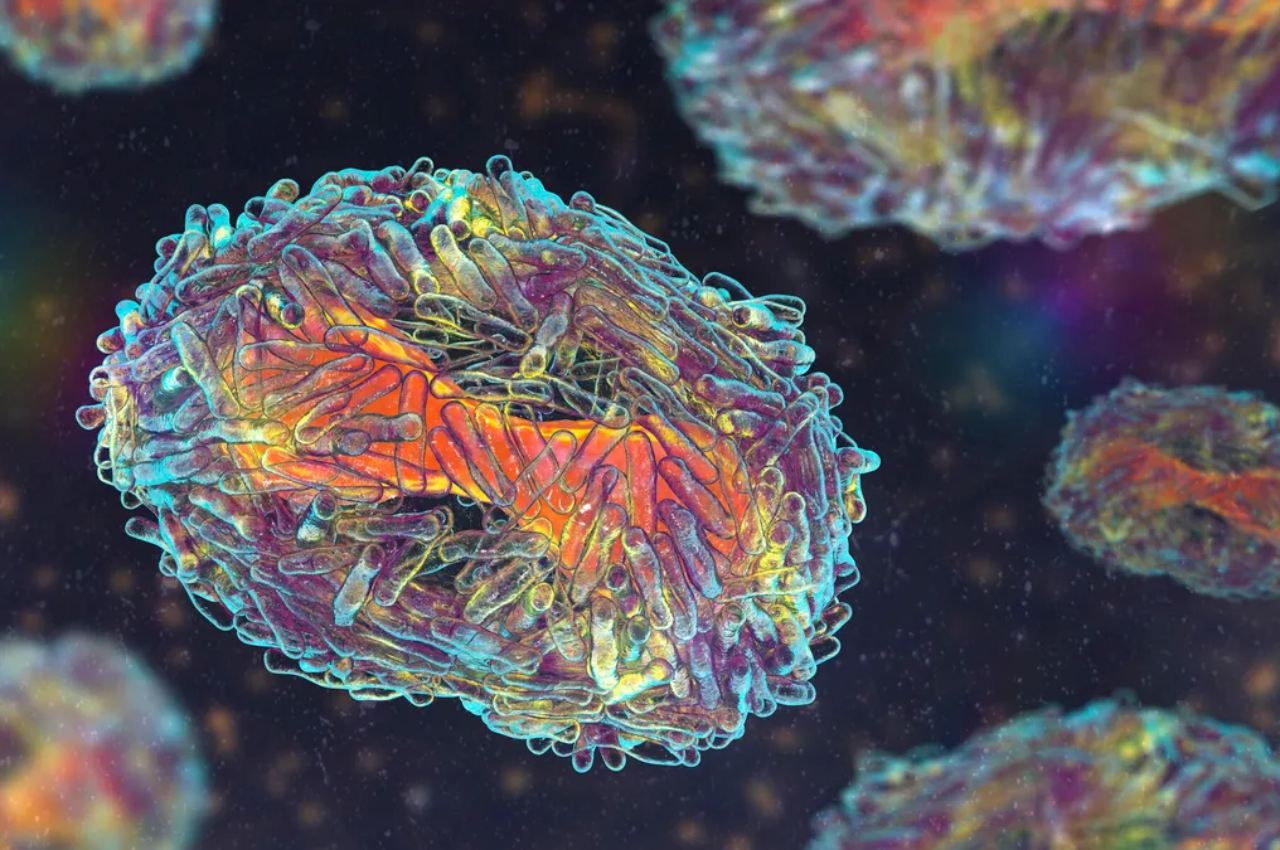

New Delhi: The United States declared monkeypox a public health emergency on Thursday, which should free up fresh finances, aid in data collection, and allow for the deployment of additional workers in the fight against the disease.

“We’re prepared to take our response to the next level in addressing this virus, and we urge every American to take monkeypox seriously and to take responsibility to help us tackle this virus,” Health and Human Services secretary Xavier Becerra said in a call.

The declaration, which initially lasts for 90 days but may be extended, was made as the number of cases countrywide surpassed 6,600 on Thursday, with almost 25% of them coming from New York state.

Due to the fact that the symptoms, including solitary lesions, might be modest, experts think the real number in the current outbreak could be substantially higher.

Approximately 600,000 JYNNEOS vaccinations, which were first created to protect against the virus related to smallpox and monkeypox, have so far been distributed in the US, but this amount is still well below the 1.6 million people who are thought to be most at risk and in need of the vaccine.

The Health and Human Services department reported last week that almost 99 percent of US infections have so far been among males who have sex with men, and this is the population that the national vaccine policy is aimed at protecting.

Contrary to earlier epidemics in Africa, the virus is currently primarily transferred through sexual activity, while the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention notes that alternative methods, such as sharing bedding or clothing or staying in close proximity for an extended period of time, are also conceivable.

The World Health Organization, which only does this for diseases of the utmost concern, also declared the outbreak an emergency last month, prompting the US designation.

Robert Califf, the commissioner of the US Food and Drug Administration, revealed Thursday that his organisation was considering a change that would enable medics to deliver five doses of the vaccine using a single dose of the current vials.

The vaccine would be given intradermally, at a shallower angle, as opposed to the existing method of subcutaneous administration.

This “means basically sticking the needle within the skin and creating a little pocket there into which the vaccine goes, so this is really nothing highly unusual,” said Califf.