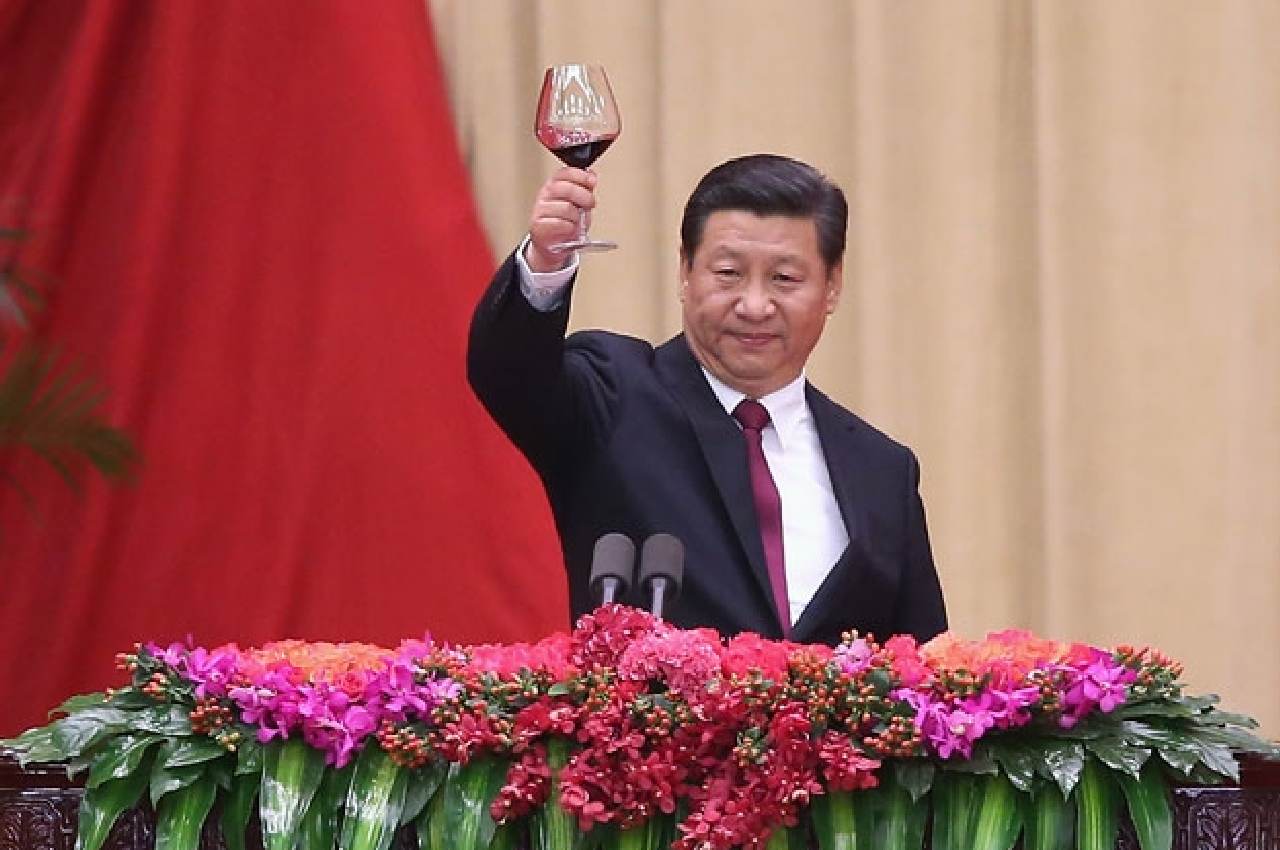

New Delhi: When Chairman Xi Jinping extend his term in power for another five years at this month’s 20th Party Congress of the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP), one other important area of interest will be the make-up of the Central Military Commission (CMC).

CMC supervises all aspects of the country’s military

The CMC is China’s highest body that supervises all aspects of the country’s military, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). There are just seven people in the CCP, with Chairman Xi Jinping at the top of the totem pole. He is aided by two vice chairmen and four other members.

Four of these six members are expected to depart the CMC since they will reach the mandatory retirement age of 68. Unless Xi overturns this regulation, the only two likely to continue on are therefore Miao Hua, the Political Work Department Director; and Zhang Shengmin, Discipline Inspection Commission Director. Both of these are experienced political commissars, so should possess purity of party loyalty.

25 potential candidates in the race

There are approximately 25 potential candidates, and former Strategic Support Force commander Gao Jin and Eastern Theater Commander Lin Xiangyang could be frontrunners for elevation to the CMC. Whomever Xi promotes to the highest military council will reveal a lot about Xi’s ambitions and priorities.

Even below this highest level, the next cohort will also be breaking through as they steer the PLA in a more high-tech and joint direction.

In the lead-up to the 20th Party Congress, some interesting details were observable at a seminar on national defense and military reform held in Beijing on September 21.

“Deepening the reform of national defense”

Headlining the event, Xi claimed that “long-standing systemic obstructions, structural incongruities and policy issues in the development of national defense and the armed forces have been resolved, while historical achievements have been made in deepening the reform of national defense and the armed forces”.

Xi urged “pioneering and innovative efforts to implement reform tasks and strengthen planning on future reforms, so as to provide strong impetus for achieving the goal set for the centenary of the People’s Liberation Army”.

Roderick Lee, Research Director at the China Aerospace Studies Institute in Washington DC, commented that the attendance list at the seminar revealed “some pretty substantive changes and may reveal some future CMC members”.

He Weidong is the top contender

The “oddest appearance” was former Eastern Theater Command Commander He Weidong, last spotted at the National People’s Congress session in March. He was seen wearing an unusual CMC-level shoulder patch. Lee suspects it was a CMC Joint Operations Command Center patch, but one has never seen before.

What is interesting about He is that he is 65 years old, and technically approaching retirement age. While it is possible that He may already be retired, and simply attended the seminar in his capacity as an NPC representative, Roderick Lee’s preferred reasoning is this: “I suspect the reason is so he can be selected as a one-term CMC vice chair like Fan Changlong. Odd, though, that he is not a representative to the 20th Party Congress,” Lee mused.

Lin Xiangyang is believed to have moved into He’s former position as Eastern Theater Command commander. Lin was previously briefly the head of the Central Theater Command before being succeeded by Wu Yanan. This would have left Lim temporarily without a suitable pick for the post.

He may either still be active in an unidentified CMC organ billet, or he could have spent a small amount of time in this billet before retiring. However, the trend of stashing three-star generals seems odd. Is it related to the promoted rank and grade at the same time?

That would relate to someone lined up to replace a soon-to-retire commander if the retirement is occurring before the next promotion ceremony.

Xu Xueqiang is the second top contender

A second individual of interest at the PLA seminar in Beijing was Xu Xueqiang, previously commandant of the PLA’s National Defense University. He too sported a CMC-level patch, and Ming Pao claimed several weeks ago that Xu might be the new director of the CMC Equipment Development Department. Li Shangfu, the current department head, was also present at the meeting. It may be that Xu is in waiting until Li retires, but this is yet to be confirmed.

Liu Zhenli is the second top contender

A third interesting individual was former PLA Army Commander Liu Zhenli. The same Ming Pao article claimed Liu might be the next Joint Staff Department chief of staff. Lee speculated that this might be true. Notably, Liu is a veteran of the 1979 war with Vietnam, meaning he is one of the few remaining combat veterans still in PLA service.

Also present was Li Qiaoming, the subject of extensive rumours that linked him to leading the imaginary coup that supposedly deposed Xi. Of course, there was no truth to such conjecture, especially considering that Li does not even control any actual forces.

Li was the Northern Theater Command commander up until a few weeks ago when he was replaced by Wang Qiang. Li now sports a PLA Army patch. Since the army’s political commissar Qin Shutong was also present, Li Qiaoming may have replaced Liu Zhenli as PLA Army commander.

Li Qiaoming’s conclusion

Li concluded: “The key takeaway: If this is the next generation of CMC-level leaders (and possible CMC members for He Weidong and Liu Zhenli), this will be the first batch with someone who has even limited joint experience (He Weidong).

However, this does not feel like a dramatic shift. It does feel like the typical blend of continuity between the last generation and the next generation. He Weidong is pretty ‘old school’, despite his time at Eastern Theater Command, but Liu Zhenli is quite young (58 years old). As such, he would be a viable CMC vice chair candidate in 2027.”

Despite all of Xi’s changes to and restructuring of the PLA, the military has continued to make do with its existing cohort of senior leaders to manage the new system.

Gray Dragons: Assessing China’s Senior Military Leadership

Joel Wuthnow, in a report called “Gray Dragons: Assessing China’s Senior Military Leadership” and published by the Institute for National Strategic Studies in the USA, recorded: “The PLA did not skip a generation of officers whose formative experiences were rooted in the Cold War to place young Turks more familiar with modern technologies and operational concepts into positions of responsibility.”

Nearly all of today’s senior leaders rose through the ranks of their own military services (army, navy, air force or rocket force), with little previous joint experience, and their careers were shaped by their own service traditions. Nor has the PLA’s gender or ethnic diversity altered, with Han Chinese dominating the senior hierarchy.

Even today, PLA senior officers only change posts every 2-3 years, unlike the average Chinese figures who have much international exposure or experience.

Wuthnow noted, “Continued specialization in particular career tracks means that they have relatively deep expertise in particular areas, but likely limited awareness of other functional skills: for instance, operational commanders tend not to have a background in logistics or acquisition.”

Nor can they progress their careers without subscribing wholeheartedly to CCP doctrine. Wuthnow remarked: “They must undergo extensive political vetting and face continuous monitoring from political commissars, the anti-corruption investigators within the CMC Discipline Inspection Commission, financial auditors and the legal system. Such control mechanisms probably induce caution in personal affairs – today’s senior officers are less overtly corrupt than their predecessors – but may also blunt risk-taking in operations as officers look up the chain of command or build consensus in Party committees.”

13,000 PLA officers were punished for corruption offences

From 2012-17, more than 13,000 PLA officers were punished for corruption offences. While much corruption has been purged, it would be a foolish person who claimed that corruption had been expunged from the PLA.

The PLA is drawing relatively equally from all theatres and group armies. It is thus protecting institutional equities, but also ensuring that breadth of expertise rises to the highest offices.

The influence of the ground forces in senior leadership positions is declining, with relatively greater representation by the air force and navy. However, when the five theatre commanders all returned to army leaders in late 2021, it proved that service diversity cannot be assumed.

Assignment system does not prioritize risk-taking

The report by Wuthnow pointed out: “PLA sources frequently advocate for officers who can think in new ways, but the assignment system does not prioritize or produce broad experience or risk-taking.” Operational commanders without a broad understanding of areas outside their expertise (e.g. logistics) could lead to poor unit cohesion, such as happened with Russian units fighting in Ukraine.

Wuthnow added: “CMC-theater coordination will be limited by a system where officers do not frequently rotate between CMC departments (where policy and training requirements are set) and the theatres (which implement CMC guidance). Such weaknesses are probably exacerbated by political work rules and organizational traditions that prize centralized authority and consensus decision-making.”

China’s Cold War strategy

Significantly, the current PLA leadership cohort is the last steeped in China’s Cold War strategy, which emphasized ground force combined-arms operations against superpowers. On the other hand, younger officers possessing formative experiences within a reformed PLA (e.g. joint training) will begin to break through in the coming years.

The American academic Wuthnow had another interesting observation. “The officers who entered the PLA in the late 1980s and 1990s do not have personal memories of the chaos of the Cultural Revolution, and are more familiar with an ascendant post-Mao China, and they are perhaps more likely to overestimate PLA capabilities and China’s prospects in a military conflict.”

Inter-service rivalry?

The removal of service chiefs from the CMC in 2017 meant that each service must appeal to a higher decision-making authority for funding and resources. Will this promote inter-service rivalry? Certainly, the CMC will be required to adjudicate and allocate resources accordingly.

It bears watching whether there will be a decrease in the average age or length of service in senior officers. If this occurs, it would indicate that the PLA that proteges well acquainted with more modern warfare are assuming greater responsibility. In the future, the PLA might increase the frequency of rotations or shift between career tracks, to improve jointness and depth of experience.

Politics play a major differentiator in the PLA

Politics play a major differentiator in the PLA compared to the US military. Nearly half of PLA senior officers are political commissars, whose purpose is to keep individuals and units loyal to the party and to fulfil CCP directives. Senior figures cannot just be experts in military affairs – they must also be “red” in nature.

Wuthnow asked, “Whether this requirement becomes a hindrance to professionalization by taking time away from military matters, or helps the party by increasing unity of thought and resolve, will be known only when the PLA leadership is put to the ultimate test, in battle.”