Pick up your smartphone, switch on a ceiling fan, or watch a missile launch on the evening news. All three rely on the same “invisible” fuel: a group of 17 chemical elements known as Rare Earths.

They sit quietly inside touchscreens, EV motors, and fighter jet radars. They are the vitamins of the modern world—needed in small doses, but without them, the body of the economy fails.

The twist? One country, China, has their hand on the tap. It dominates the mining, processing, and magnet-making that turn these rocks into geopolitical power. For India, aspiring to be a $5 trillion manufacturing superpower, this is not just a supply chain detail. It is a structural choke point.

This explainer cuts through the jargon to tell you why “sand” is the new “oil,” and how India is finally fighting back.

What exactly are rare earths?

Rare earth elements are a family of 17 metals, mainly the lanthanides, along with yttrium and scandium. Chemists love them because they are magnetic, heat-resistant and excellent at handling light. Engineers love them because they make gadgets smaller, lighter and more efficient.

They are called “rare” not because they are extremely scarce in the earth’s crust, but because they are rarely found in concentrated, easy-to-mine deposits. They usually come mixed with other minerals and often with radioactive elements, which makes mining and processing messy, expensive and environmentally sensitive.

According to the latest US Geological Survey data, global rare earth mine output in 2024 was around ~390,000 metric tonnes of rare earth oxide equivalent.

Where do we use them in everyday life?

You may never see them, but rare earths quietly power modern life:

⦁ Smartphones and laptops

Neodymium and dysprosium help make the tiny but powerful magnets inside speakers, vibration motors and hard drives.

⦁ TVs and LEDs

Europium and terbium give the sharp reds and greens in screens and energy efficient bulbs.

⦁ Electric vehicles and wind turbines

Neodymium and praseodymium magnets are at the heart of many EV motors and direct-drive wind turbines, making them lighter and more efficient.

⦁ Medical and clean-tech equipment

MRI machines, high efficiency generators, industrial robots and data centres all rely on rare earth magnets and materials.

⦁ Defence and space

Guidance systems, radars, sonar, precision missiles and satellites use rare earth based magnets and special alloys because they work reliably in extreme conditions.

For India’s energy transition, rare earths are the “vitamins” of clean tech. You need only a few grams in each device, but without them the whole system performs worse or becomes bulkier and costlier.

How did China become the rare earth superpower?

Over three decades, China followed a clear strategy: offer cheap supply, capture the entire value chain and then slowly tighten its grip.

⦁ By 2024, China accounted for around 69 percent of global rare earth mine production, far ahead of the United States and other producers.

⦁ More importantly, China controls an estimated 80 to 85 percent of global rare earth processing capacity that turns raw ore into refined oxides and metals.

Mining is only the first step. The real choke point is processing and magnet manufacturing. China has built deep expertise and capacity in both, while other countries allowed their own industries to wither.

This dominance is no longer just an economic advantage; it is also a strategic lever. In 2023, Beijing banned the export of certain rare earth extraction and separation technologies, making it harder for others to build competing processing industries. CSIS In 2025 it further tightened controls on some rare earth magnets, in part as a response to new tariffs on Chinese goods.

The message to the world is simple: if you depend on China for rare earths, you are also exposed in any trade or geopolitical dispute.

India’s dilemma: rich in reserves, poor in value addition

Here is the paradox. India is not a small player on paper.

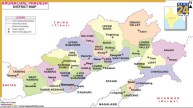

⦁ A recent CareEdge analysis estimates that India holds around 8 percent of the world’s rare earth element reserves, mostly in monazite sands along the coasts of Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh and Odisha.

⦁ Yet India contributes less than one percent of global rare earth production and exports mainly low value compounds instead of high value magnets and components.

India’s rare earth story has been shaped by nuclear policy. Monazite, the main rare earth bearing mineral in Indian beach sands, also contains thorium, which is classified as a strategic nuclear material. That brought rare earth mining and processing under tight state control.

Today, Indian Rare Earths Limited (IREL), a public sector company under the Department of Atomic Energy, is the only entity that processes monazite to produce rare earth compounds at scale. It has the capacity to process about 10,000 tonnes of rare earth bearing mineral per year, but actual monazite production has been closer to 4,000 tonnes due to constraints like mining leases, environmental and coastal regulation zone clearances and land issues.

At the same time, India imports large volumes of finished rare earth permanent magnets used in electric motors, electronics and defence equipment. In FY25, India imported over 53,000 tonnes of rare earth permanent magnets, and demand is expected to double by 2030.

In simple language, we have the raw material under our sand, but we pay others for the most expensive part of the value chain.

India’s new playbook: from sand to strategic autonomy

In the last two years, New Delhi has started treating rare earths like a strategic asset, similar to oil in the twentieth century or semiconductors today.

⦁ National Critical Mineral Mission (NCMM)

In January 2025, the government launched the National Critical Mineral Mission with an outlay of 34,300 crore rupees over seven years. The mission covers exploration, domestic production, processing, recycling and overseas acquisition of critical minerals, including rare earths.

The Geological Survey of India has been tasked with 1,200 exploration projects up to 2030-31, while PSUs are encouraged to invest abroad.

⦁ Focus on processing, not just mining

Policy thinking has shifted from digging more sand to building refining and separation capacity. Recent analysis suggests India is targeting 2,000 to 3,000 tonnes of refined rare earth oxide output in FY 2025-26, with upgraded facilities at IREL and allied units.

This is still modest on a global scale but marks a move up the value chain.

⦁ Big push for rare earth permanent magnets

Just this week, the Union Cabinet approved a 7,200 crore rupee production linked incentive (PLI) scheme to set up integrated plants for rare earth permanent magnets, with total capacity of 6,000 tonnes per year.

Up to five companies will be selected through global bidding. The aim is to sharply reduce magnet imports for EVs, wind turbines, consumer electronics and defence platforms, and eventually become an exporter.

⦁ Overseas tie ups and friendshoring

Through ventures like KABIL (a joint venture of NALCO, HCL and MECL), India is exploring critical mineral assets in countries such as Argentina and Australia, while also engaging in Quad and India US cooperation frameworks on critical minerals and clean energy supply chains.

⦁ Recycling and circular economy

NCMM also explicitly talks about recovering rare earths from end of life products such as discarded electronics, EV batteries and wind turbine components, which can reduce dependence on imported ore over time.

Why this matter to every Indian

For a homemaker, rare earths may look like a distant topic, but they affect everyday life in three ways:

⦁ Prices and availability of gadgets

If rare earth supplies are disrupted or prices spike due to geopolitical tensions, it can make smartphones, TVs and appliances more expensive or harder to get. We saw similar ripple effects during chip shortages.

⦁ Jobs and pollution at home

If India builds a responsible rare earth industry, it can create skilled jobs in coastal and industrial regions. But if environmental safeguards are weak, mining and processing can damage local ecosystems and livelihoods. The policy choice is not just about minerals; it is about people.

⦁ Energy bills and climate stability

Cheaper and secure access to rare earths lowers the cost of wind, solar and EV technologies, which in turn affects long term energy costs and the pace at which India can move away from fossil fuels.

For strategists, the message is sharper. Rare earths sit at the intersection of defence, clean tech, electronics and trade policy. China’s continuing dominance, even as the United States and others try to catch up, means supply risk is not going away soon. By 2030, China is still projected to supply about 60 percent of rare earths used in magnets globally, and over 90 percent of heavy rare earths for Western demand.

India’s new mission, PLI scheme and overseas partnerships signal that rare earths are moving from a technical topic to a strategic theme, similar to what happened earlier with solar modules or semiconductors.

The road ahead: from dependence to smart interdependence

India will not replicate China’s rare earth model. Our environmental norms, democratic politics and starting position are different. But that does not mean we are condemned to permanent dependence.

The real opportunity is to build what might be called “smart interdependence”:

⦁ Enough domestic mining and processing to secure critical needs.

⦁ Deep partnerships with trusted countries for diversified supply.

⦁ Strong recycling and innovation so that we use less but get more value.

⦁ Transparent governance so that coastal communities and workers share in the benefits.

Rare earths are the hidden thread connecting a teenager’s gaming console to a soldier’s radar, and a farmer’s solar pump to a city’s metro train. As India races toward a five trillion-dollar economy and a net zero future, these quiet minerals will matter more, not less.

The question is no longer whether rare earths are important. It is whether India can move fast enough, with care for both people and planet, so that our future is not hostage to any single country’s monopoly.