When India speaks about its youth, it does so in superlatives.

The youngest large population in the world.

The fastest growing major economy.

The next engine of global growth.

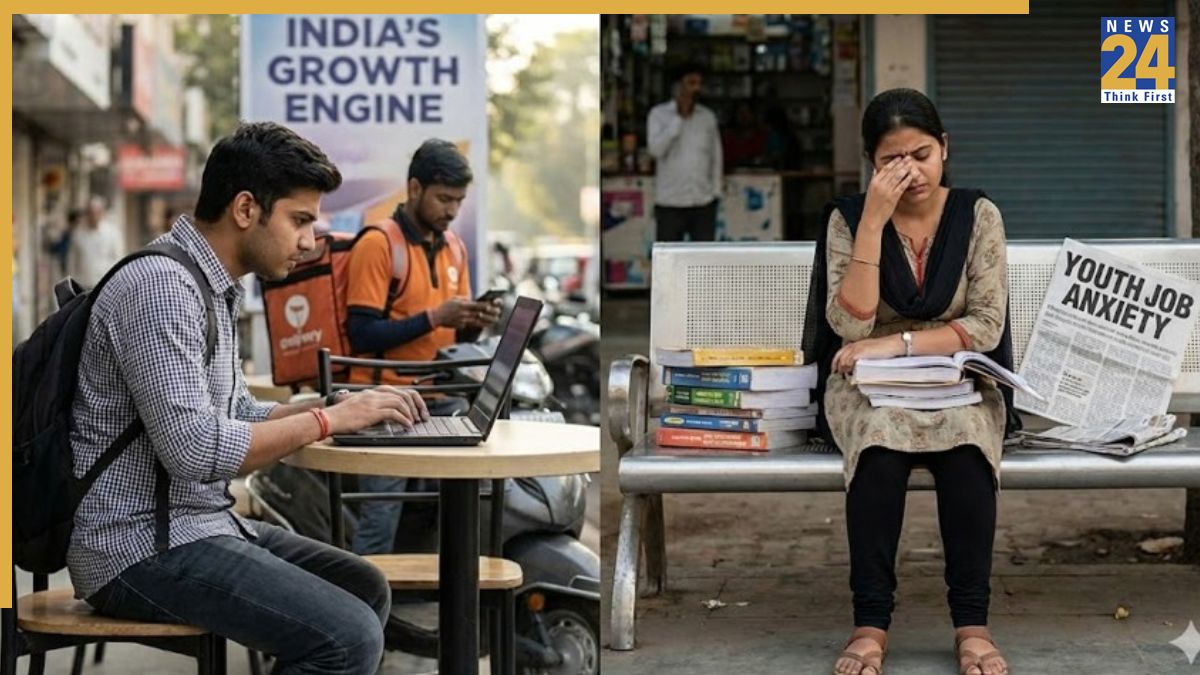

But behind these slogans lives a very real 22-year-old in a Tier-2 town, juggling a college degree, a gig job, an EMI on a smartphone, family expectations, and a persistent, unspoken question: Will I ever really make it?

This widening gap between promise and lived reality is the true story of India’s demographic dividend in 2025. It is a story best understood not only through GDP charts, but through jobs, mental health, and what all of this means for the economy and investors.

This is that story, grounded in the latest government and multilateral data, but told as a human reality rather than a spreadsheet.

1. The promise: a young country in an ageing world

India remains one of the youngest major countries globally. The median age is around 28, and nearly two-thirds of the population falls within the working-age bracket of 15 to 64. By 2030, this share is projected to rise to about 67 percent.

On paper, this should translate into faster economic growth, higher savings, stronger investment, and a massive consumer market. For investors, this forms the core India thesis: a young workforce, rising aspirations, and decades of consumption ahead.

But a demographic dividend is not automatic. It has to be earned. And that is where cracks begin to appear.

2. The jobs paradox: growth at the top, anxiety at the bottom

According to the Periodic Labour Force Survey, youth unemployment in the 15 to 29 age group stood at 10.2 percent in 2023–24. This is lower than the global youth unemployment rate of about 13.3 percent reported by the ILO.

On paper, which looks encouraging. On the ground, it feels very different.

2.1 The NEET generation and the “exam economy”

The India Employment Report 2024 shows that around 28.5 percent of Indian youth are not in employment, education, or training. Nearly three out of ten young people are effectively stuck in limbo.

In everyday conversations across small towns and cities, the phrases repeat themselves: “preparing for exams”, “helping at home”, “trying to find something”. This is not idleness. It is structural stagnation.

What is often overlooked is the scale of India’s exam economy. Each year, an estimated 2 to 3 crore unique applicants sit for government exams across Railways, SSC, UPSC, state PSCs and other agencies, competing for fewer than 1 to 2 lakh vacancies. Millions of young people spend their most productive years waiting, repeating attempts, and postponing entry into the workforce. This waiting period represents one of India’s largest hidden productivity losses.

2.2 Educated but unemployed.

PLFS data reveals a paradox: unemployment rates are highest among those with secondary and higher education. For decades, families were told that more education guaranteed stability. Instead, many graduates now find themselves in underpaid gig roles, short-term contracts, or service jobs with little security.

For middle-class households that invested heavily in education, this feels like a broken promise.

2.3 The informal and self-employed pivot

India’s employment structure is shifting. The share of self-employed workers rose from 52.2 percent in 2017–18 to 58.4 percent in 2023–24, while casual labour declined. Some of this reflects genuine entrepreneurship. Much of it, however, reflects necessity.

Driving for platforms, running micro-online businesses, or freelancing without health insurance, provident fund, or job security is often classified as self-employment. It keeps people working, but vulnerable.

A related nuance is unpaid family labour, particularly among women. PLFS 2023–24 shows that roughly 37 percent of employed women are classified as unpaid helpers in household enterprises. They are counted as employed yet earn no direct income. The employment numbers rise, but the human dividend, in monetary terms, does not.

At the same time, nearly 61 percent of net payroll additions in the organised sector are going to people below 29. This creates a sharply split youth economy: a smaller group entering stable formal jobs, and a much larger group cycling through insecure or invisible work. It is efficient for balance sheets, but emotionally expensive for people.

3. The silent crisis: mental health and distress

In 2023, India recorded 171,418 suicides, roughly 470 deaths every day. Students, young adults, and daily wage earners form a disproportionately high-risk group. Separate studies suggest that over 13,000 students die by suicide each year, a trend that has persisted for years.

The scenes behind these numbers are familiar: coaching hostels in Kota, homes after failed exam attempts, call centres with rising targets and stagnant wages.

Official records cite exam stress, family conflict, financial distress, addiction, illness, and isolation as key drivers. When this data is layered over the NEET and exam economy numbers, a disturbing picture emerges of prolonged pressure without relief.

In a society where success is measured by marks, salary, and marriage, there is little space for failure without shame, rest without guilt, or help without stigma.

4. Rural and small-town youth: the invisible majority

Much of India’s youth lives outside metros, where agriculture remains the fallback and local industry is limited. Migration becomes the default career plan, feeding coaching hubs, industrial belts, and overseas labour markets.

For many families, the aspiration is modest: one stable government or private job that can uplift the household. When that does not materialise after years of effort, the pressure becomes emotional as much as financial. Parents feel they have failed. Children internalise that failure.

This is not just an economic issue. It is about dignity, identity, and meaning.

5. Resilience amid strain

Despite these constraints, young Indians continue to push forward. There is a visible rise in startups, creators, freelancers, women entering services and manufacturing, and youth-led social initiatives. Digital public infrastructure, affordable smartphones, and cheap data have given today’s youth tools their parents never had.

Even a delivery worker in a small town may be investing, learning online, or upskilling at night. The story is not only despair. It is a constant tug of war between structural limits and individual resilience.

The question is whether policy and capital will strengthen that resilience or quietly extract from it.

6. Why this matters for investors

Youth are the backbone of future returns. A financially secure young population drives housing demand, durable goods, healthcare, travel, and stable consumption. A stressed and underemployed youth base leads to weak discretionary spending, higher credit risk, and political volatility.

The rise of Gen Z debt and buy-now-pay-later stress in cities is an early warning.

Sectors that sit at the intersection of pain and opportunity include skilling and apprenticeships, mental health services, women-centric employment solutions, Tier-2 infrastructure, and career-focused education platforms. The ethical question for investors is whether growth will be extractive or empowering. Capital that builds capability earns trust and longevity.

7. Five shifts India urgently needs

India must move from exam obsession to multiple career pathways, treat mental health as basic infrastructure, restore dignity to vocational work, place women at the centre of employment strategy, and invest in cleaner, more granular youth data.

Ignoring these shifts is not only socially costly. It is economically irrational.

8. The India young people deserve

India often tells its youth that they are the future. The harder question is what kind of country is being built for them today.

One where a 19-year-old must choose between coaching debt and family debt, or one with multiple dignified pathways to learn, work, and rest.

The demographic dividend will not be decided by GDP alone. It will be decided by whether a young Indian, in a village or a metro, can look ten years ahead and say something simple: I have a fair chance.

If that becomes true for most, India’s dividend will not just be demographic. It will be deeply human.