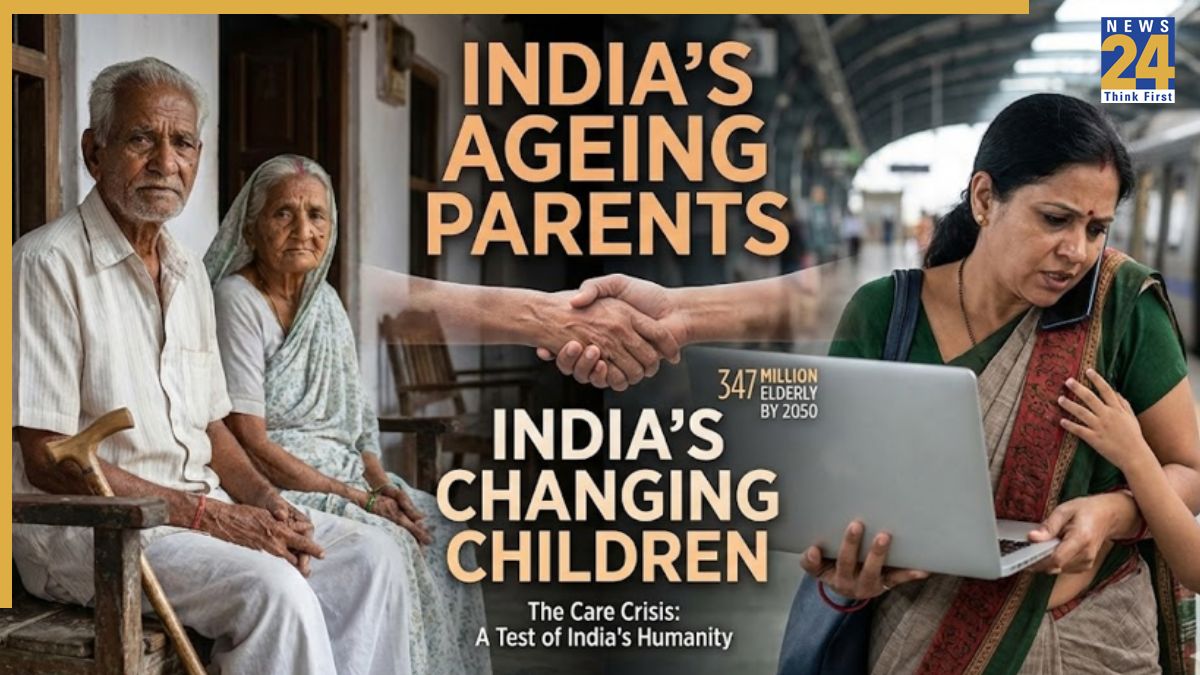

Why the care crisis is the next big test of India’s humanity

India loves to describe itself as a young country, but inside millions of homes another reality is unfolding. Parents are living longer, children are busier and often far away, and the old idea of “joint family care” is eroding without a replacement ready.

According to the United Nations Population Fund, India already has about 153 million people aged 60 and above, projected to reach 347 million by 2050. That means nearly one in five Indians will be elderly within the working lifetime of today’s adults. This is not just a demographic shift; it is a civilisational moment. How India treats its ageing parents will reveal more about our values than any GDP number.

The quiet demographic turn

For years, the focus remained on the demographic dividend, but the same datasets now show how fast the age pyramid is tilting. India’s elderly share was 8.6 percent in 2011 and will rise to around 20 percent by 2050. NITI Aayog notes that India already has over 10 percent of its population classified as senior citizens and this group is ageing at one of the fastest rates in the world.

The transition is uneven. Southern and western states, and some northern states like Himachal Pradesh and Punjab, have a higher elderly share and will age faster. Poorer heartland states will age with weaker incomes and less robust public services. India will soon be a country with a young labour force abroad, a stretched middle aged workforce at home, and a rapidly expanding population of vulnerable elders who need care and dignity.

Ageing in India looks very different depending on where you stand

The Longitudinal Ageing Study in India, tracking more than 70,000 older Indians, shows how many chronic illnesses go undiagnosed. About 16 percent of those over 60 have diabetes based on blood tests, but only 14 percent self report it. Around 8 percent of adults over 45 have undiagnosed diabetes, and anaemia affects about 34 percent of older men and 40 percent of older women.

Behind these numbers are everyday realities: a retired schoolteacher avoiding tests due to cost; a widow living with untreated hypertension because the nearest specialist is far away; an elderly couple in a city relying on video calls and part time help because their children live abroad.

Research on elder abuse reveals another layer of vulnerability. One national survey found high levels of hidden mistreatment within families, ranging from verbal humiliation to financial exploitation and physical abuse. Elderly women, widows and those with low education face the highest risk. Many Indians are living longer lives, but not necessarily healthier or more secure lives.

The invisible labour holding ageing India together

Who looks after the elderly today? Mostly women, mostly unpaid, mostly unrecognised.

The Time Use Survey 2019 found that 82.1 percent of rural women and 79.2 percent of urban women participate in unpaid domestic work daily, compared to much lower male participation. A significant share involves caring for children, the sick and the elderly. A 2025 follow up survey shows women aged 15 to 59 still spend about five hours a day on unpaid domestic work despite more joining the workforce.

This means a typical middle aged Indian woman today is managing ageing parents or in laws with chronic illnesses, raising children, handling household work and trying to maintain a job. It is a classic “sandwich generation” crisis. Recent caregiving studies confirm this strain, showing that elderly individuals dependent on daily support rely heavily on informal caregivers whose needs are rarely addressed in policy.

We talk about “seva” and “sanskar”, but rarely about who bears their cost.

Cities, climate and the fragile comfort of old age

Urban India adds new risks. The World Bank estimates Indian cities will need about 2.4 trillion dollars in climate resilient infrastructure by 2050 to cope with heatwaves, floods and climate shocks. Heatwaves hit elders the hardest. Floods trap those with mobility limits. Poor ventilation and crowding raise infection risks for seniors with weak immunity.

Climate resilience and elder care are deeply intertwined. Every failure in drainage, heat action planning or urban accessibility lands on the shoulders of elderly citizens first.

The rise of the silver economy: gain for some, gap for many

India’s senior care market, valued at 10 to 15 billion dollars today, could reach 30 to 50 billion dollars in the next decade. Urban India is seeing rapid growth in senior living facilities, assisted living apartments, home health platforms, wearable emergency devices and subscription based “elder concierge” services. Reports show senior living alone could become a multi billion dollar segment by 2030.

This brings gain: new jobs in nursing and home health, new business models in housing and insurance, investor opportunities in long horizon services.

But it also exposes gaps. Premium assisted living in large cities has no counterpart for a widowed farm worker in Bundelkhand or a retired factory worker in Kanpur. Public pensions remain tiny. Affordable, high quality long term care institutions are rare. Without strong public policy, the silver economy risks becoming an island of comfort for a small fraction of India’s elderly while most depend on overstretched families.

What the state has done, and where gaps remain

India has introduced important frameworks: the Maintenance and Welfare of Parents and Senior Citizens Act, the National Policy on Older Persons, old age pensions, subsidised healthcare and senior citizen concessions. NITI Aayog’s senior care reform framework calls for integrated health and social care models.

But implementation gaps persist. Many elderly citizens do not know their entitlements. Pension amounts are too small and irregular. Primary health centres are not equipped for chronic disease and dementia care. Long term care infrastructure remains thin outside major cities. Ageing is acknowledged on paper but treated as a private family responsibility in practice.

A more humane ageing agenda for India

A rights-based approach offers clear priorities.

Make primary healthcare geriatric friendly: Routine screening for diabetes, hypertension, cognitive decline, vision and hearing should be integrated into primary care. Frontline workers should be trained to recognise elder abuse, caregiver burnout and mental health concerns.

Recognise and support caregivers: Time Use Survey data should inform social protection for unpaid caregivers, including pension credits or insurance benefits linked to years of caregiving. Community based respite and day care centres can relieve families.

Expand affordable senior care: Incentivise development of low and middle income assisted living options at district level. Establish quality standards for old age homes so they do not become neglect zones.

Build ageing into climate and urban planning: Heat action plans, transport design and housing policies must account for elders. Physical and digital accessibility should improve.

Strengthen income security: Gradually raise pension levels and improve delivery, especially for single, widowed and disabled elders. Encourage simple long term savings instruments for informal workers.

Change the narrative: India must move beyond the images of the “burden” elder and the “super senior achiever”. Most seniors live in the middle, negotiating everyday challenges: climbing a bus step with arthritic knees, managing UPI with fading eyesight, missing children abroad while pretending to be fine.

The real question India must answer

India will have hundreds of millions of elderly citizens within the next 25 years. The demographic direction is set. The real question is simple: will those extra years of life be marked by suffering or dignity?

If ageing is treated only as a cost, families will crack under pressure, women will lose economic freedom, and elders will fade into the margins of fast moving cities.

If ageing is treated as a shared human project, India can build a future where longer life expectancy brings longer years of meaningful work, intergenerational learning, community belonging and opportunity in the silver economy.

India’s ageing story is not about “them”. It is about all of us, just a few decades from now, asking whether we built a society where our parents aged with dignity or where we hoped someone else would care for them.

How we decide today will determine whether our added years become a gift or a warning.