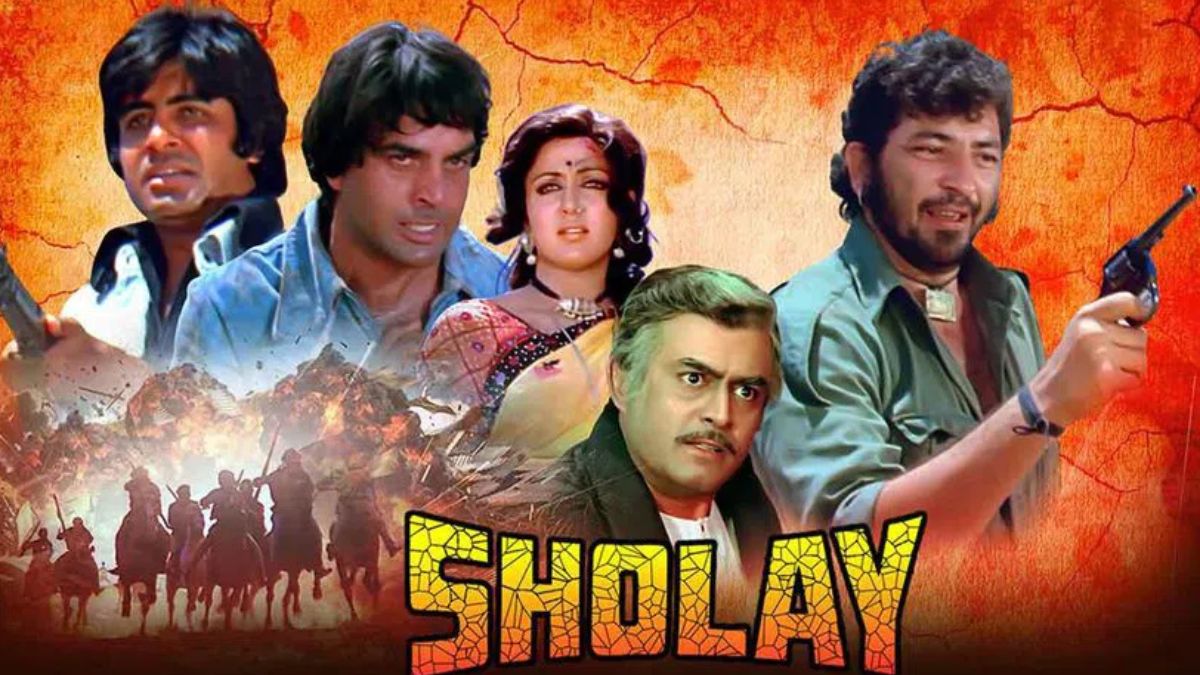

When Sholay was released in theaters in 1975, it was not another Hindi film—it was a phenomenon. People were enthralled by its taut screenplay, punchy dialogue, and irrepressible characters. But all this homegrown magic disguised a mosaic of global cinematic influences.

From the arid plains of Sergio Leone’s Italy to Japan’s samurai villages, Sholay borrowed and reinterpreted concepts from world cinema and infused them with a distinctly Indian flavour.

Let’s pull back the curtain and follow the DNA of this classic.

1. The Leone Legacy – A Villain’s Great Entrance

Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West provided audiences with one of the most chilling first introductions to a villain ever put on film. Henry Fonda’s character walks in with false aplomb, only to slaughter a whole family.

In Sholay, Ramesh Sippy created Gabbar Singh’s initial appearance with the same slow-burning tension. The calm before the storm, the insidious sense of foreboding, and then – abrupt, brutal violence on Thakur Baldev Singh’s family. It’s a harsh introduction to the world of Gabbar, and it owes a debt to Leone’s skill at turning cruelty into cinema.

2. Spaghetti Westerns – Dust, Guns, and Standoffs

The DNA of the Spaghetti Western pervades Sholay. Ramanagara’s desert landscapes serve as the American frontier, with dust clouds swirling in the heat as gunslingers eye each other up. Jai and Veeru are not merely petty thieves – they’re Bollywood’s equivalents of Leone’s wandering bounty hunters.

From vengeful showdowns to the stylized close-ups on eyes, flicking hands, and glinting guns, Sholay takes the syntax of the Western but uses it in Hindi. Even its rhythm in standoffs follows the charged silences of the genre, ratcheting up tension until the first shot is fired.

3. Outlaws With Wit – Lessons From Butch Cassidy and Co.

If Jai and Veeru’s repartee comes so naturally and endearingly, it is because their rapport embodies the essence of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. The good-natured deriding, the implicit faith in each other, and the natural laughter in the midst of adversity all bring back memories of the Paul Newman–Robert Redford duo.

The impact of Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid also seeps in through betrayals and loyalties in an outlaw society. And in gunfights, Sholay’s rare slow-motion scenes carry the hallmark of The Wild Bunch—violence as much as action, but spectacle too.

4. Seven Samurai – The Heart of the Story

Beneath its top-drawer melodrama and top-billing, Sholay’s plot is a very different tradition: Japanese. Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai had the villagers hiring warriors to protect them from bandits—a story so universal that it’s been retold, at least, by Hollywood in The Magnificent Seven.

In Sholay, rice paddies give way to dusty plains, and the samurai are replaced by gunslingers. The enlistment of Jai and Veeru is reminiscent of Kurosawa’s judicious recruitment of guardians, while the villagers’ cause holds on to that same mortal, human desperation.

5. The Good, the Bad and the Ugly – Showdowns and Suspense

Leone’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly honed the discipline of the gunfight—protracted silences, close-ups with faces inches apart, and music that grips the nerves tighter. Sholay plagiarizes this beat for the shootouts, using silence and looks to make the bullets talk.

Even the uncomfortable alliance of Jai and Veeru, with all the greeds, loyalties, and mutual respect, seems like it might have strolled off the set of a Western saloon.

6. A British Detour – The Train Ambush

Not all of the influences on Sholay were Wild West. North West Frontier, a 1959 British film, has an intense train ambush with horseback attackers, passengers in jeopardy, and a battle waged at high speed. Ring any bells?

Sippy’s initial train scene, when Gabbar’s men attempt to wreck and plunder, echoes that same sense of disarray and danger – horses thundering down the sides, peril closing in, and heroes battling to protect the passengers.

A Global Movie in Indian Attire

What makes Sholay remarkable is not just that it borrowed from so many sources – it’s that it reinvented them. Sippy and his crew took the toughness of the Western, the framework of a samurai saga, and the intensity of action films, then grafted on Indian music, melodrama, and emotional complexity.

The payoff: A movie that is both universal and recognizably local, appealing to small-town Indian audiences while winking in recognition at cineastes who have seen its influences.

Almost half a century on, Sholay continues to be a testament to the global nature of film-evidence that good storytelling can hitch a ride from any corner of the world, provided it gets into good hands.

ALSO READ: Ramesh Sippy On 50 Years Of Sholay: Why the Original Ending Was Never Shown