The biggest strength of this gritty espionage thriller is also its primary weakness. So real and bleak is the world of espionage created by writer-director Mani Shankar, that you wonder if the sheer sexiness of being a spy that we saw Dharmendra and Tom Cruise experience in “Aankhen” and “Mission Impossible” was a cinematic hoax created to hoodwink us into believing in the heroic hi-jinks of people who risk their lives for the sake of national security.

“Mukhbiir” creates a universe of continual searching and annihilation, where heroes are made and unmade with the passage of one bullet from gun to temple, and God help the temple.

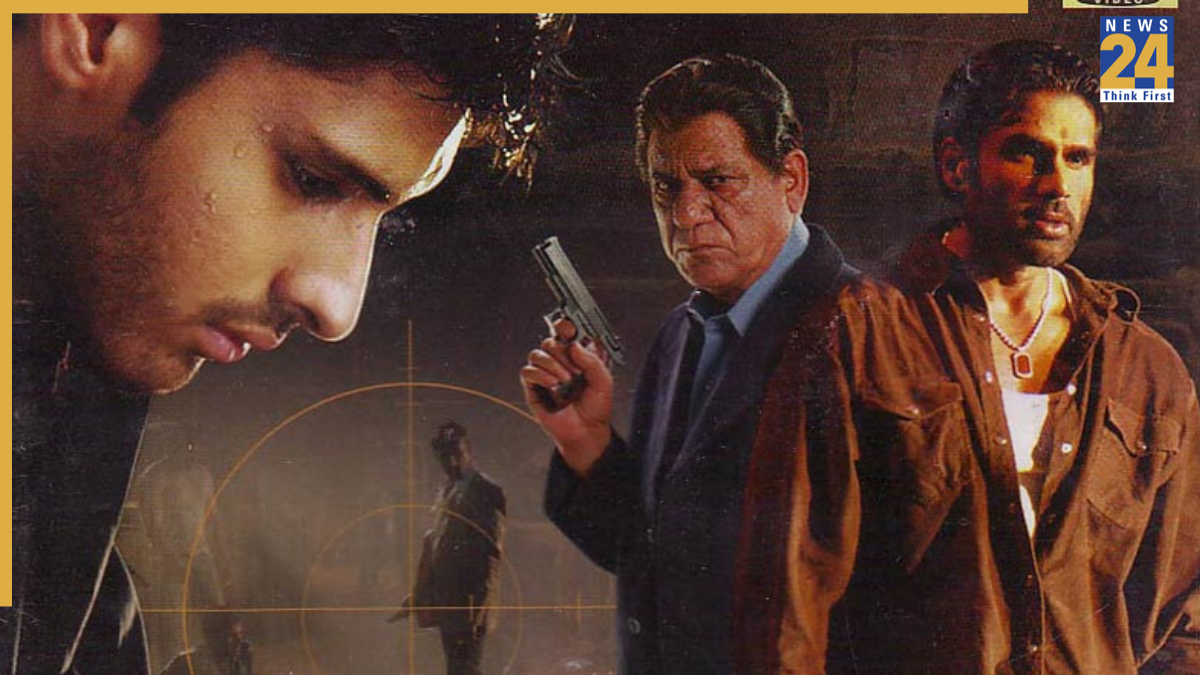

The young protagonist Kailash (Sammir Dattani) is young, vulnerable, and so brutally thrown from one ruthless organisation to another (legitimate or otherwise) that at the end of his anguished journey in search of a self-identity, we want him to be liberated of the pain that seems to be his only constant companion.

The characters come and go in episodic eruptions. Silence is Kailash’s final ally. What “Mukhbiir” does to the spy genre is to turn it inside out. We aren’t looking at James Bond’s stirred-and-sexy world of the spy who loved the good life. “Mukhbiir” takes us into the murkiest depths of the espionage business where survival isn’t a craving. It’s a fugitive option offered to a few lucky ones.

Luckily, for the gripping and gritty script, the protagonist is a boy-man constantly thrown into situations of severe uncertainty and terror. The tension never slackens.

The reluctant young spy survives by sheer instinct and guts. The screen time is segregated into various episodes from Kailash’s life as a government informer in action. The shoot-outs, somewhat amateurish in their chaotic eruptions, do not define the protagonist’s life as much as the human contact.

Every encounter written for Sammir Dattani’s character creates a new level of existential summit in his doomed life until we come to the finale where on Kailash’s life (and death) hinges the survival of a city.

The director fills up the awkward ill-defined spaces in the narrative with pockets of humour and bridled drama, all signifying the dynamics of an individual life’s relationship with a troubled and violent society.

Mani Shankar’s storytelling is highly original. There’re no false moments in the discursive yet clenched drama of dissociation where Kailash becomes so distanced from his original identity that he eventually forgets who he is. The powerful script lets us know there is no mercy for the weak in this grim and unsettled world of espionage and extremism. The two fatally-compatible worlds meet in strange eerie places where Kailash’s masquerade as a man removed from his natural roots is so complete you wonder if he can ever go back to a ‘normal’ life.

Immense warmth and empathy are created in Kailash’s interactions with people like his mentor Om Puri, who first tutors Kailash into being a mean machine and then lets the poor boy loose in a world where death is the only certainty.

Also Read: 17 Years Of Bobby-Irrfan-Priyanka Chopra’s ‘Chamku’

Alok Nath, Suniel Shetty, Raj Zutshi, and Sushant Singh play various other characters, who come in and out of Kailash’s life, with wonderful warmth or wickedness. There’s also a bit of diverting romance in Kailash’s life when the pretty Raima Sen shows up for a while and departs, leaving the desolate protagonist to his own devices.

But it’s the mentor-turned-tormentor Om Puri’s relationship with the boy-man-misinformed-informer that holds the plot together, providing it with a sensitive centre.

The sequence where the Mukhbiir must watch his mentor being tortured and then kill him with his own hands without giving the game away is devastating in its intensity and impact.

Mani Shankar’s narration provides the hero’s journey from disembodied salvation to abject doom and near-damnation with an energetic reined-in adrenaline that flows across the narrative’s veins in restrained motions.

What you go away with is the protagonist’s pain, heartbreak, vulnerability, and an untraceable reserve of inner strength that he uses to survive in a constantly treacherous world. The doom and the doomed eventually merge into one in “Mukhbiir”.

Recalls Mani Shankar, “I first encountered them in Kashmir in ‘96. Young men from broken families with nowhere to go. Canon fodder for agencies to exploit. The agency gives them some money, an identity, a false sense of protection, and deploys them in the most dangerous of situations—deep inside enemy territory. The life span of a Mukhbir ranges from a few weeks to a few months. When they are caught they are interrogated, tortured, and killed. If they manage to survive, they are sold down the line by their own mentors—as barter in exchange for more vital info. These brave young men unwittingly serve to keep a nation safe. The ‘human Int’ they gather is vital to national security. They are un-honoured, unsung heroes who deserve to be recognised—incognito at least. Me and my co-writer Anjali Joshi mulled on this subject for years, looking at every angle, researching, meeting people—and nearly a decade later the script was ready. Sammir Dattani looked perfect for the part—young, good looking, and innocent. But it takes a serious actor to play naive without looking unintelligent. Sammir expanded on the subtext, internalised his role, and performed marvellously. Mukhbir is a most significant film and I’m proud of it. Om Puri and Suniel Shetty gave the movie the added punch it needed. Raima Sen performed her cameo brilliantly, and the antagonist Rahul Dev came out with an amazing performance.”

Also Read: Nila Madhab Panda’s ‘Kaun Kitne Paani Mein’ Clocks 10 Years